gRPC Load Balancing

This post describes various load balancing scenarios seen when deploying gRPC. If you use gRPC with multiple backends, this document is for you.

A large scale gRPC deployment typically has a number of identical back-end instances, and a number of clients. Each server has a certain capacity. Load balancing is used for distributing the load from clients optimally across available servers.

Why gRPC?

gRPC is a modern RPC protocol implemented on top of HTTP/2. HTTP/2 is a Layer 7 (Application layer) protocol, that runs on top of a TCP (Layer 4 - Transport layer) protocol, which runs on top of IP (Layer 3 - Network layer) protocol. gRPC has many advantages over traditional HTTP/REST/JSON mechanism such as

- Binary protocol (HTTP/2)

- Multiplexing many requests on one connection (HTTP/2)

- Header compression (HTTP/2)

- Strongly typed service and message definition (Protobuf)

- Idiomatic client/server library implementations in many languages

In addition, gRPC integrates seamlessly with ecosystem components like service discovery, name resolver, load balancer, tracing and monitoring, among others.

Load balancing options

Proxy or Client side?

Note: Proxy load balancing is also known as server-side load balancing in some literature.

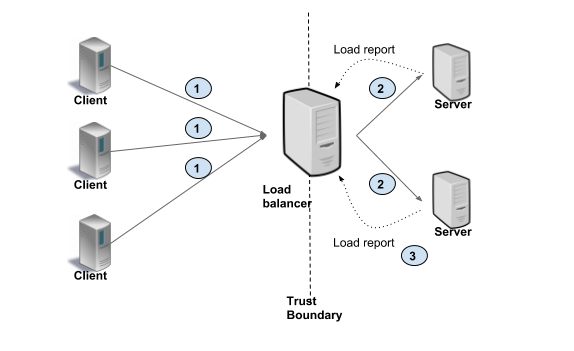

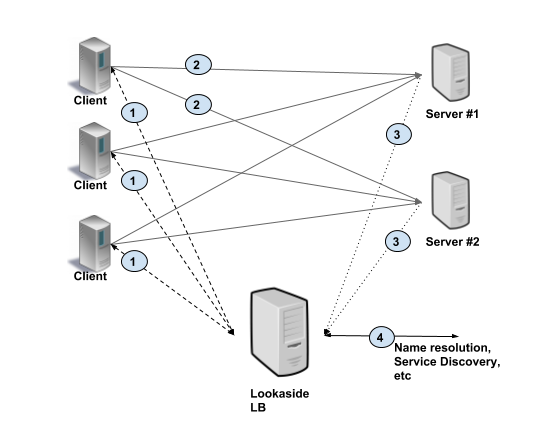

Deciding between proxy versus client-side load balancing is a primary architectural choice. In Proxy load balancing, the client issues RPCs to the a Load Balancer (LB) proxy. The LB distributes the RPC call to one of the available backend servers that implement the actual logic for serving the call. The LB keeps track of load on each backend and implements algorithms for distributing load fairly. The clients themselves do not know about the backend servers. Clients can be untrusted. This architecture is typically used for user facing services where clients from open internet can connect to servers in a data center, as shown in the picture below. In this scenario, clients make requests to LB (#1). The LB passes on the request to one of the backends (#2), and the backends report load to LB (#3).

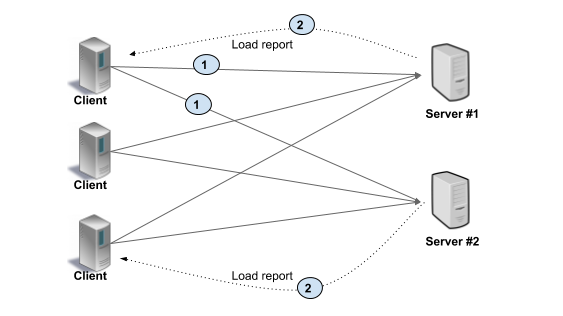

In Client side load balancing, the client is aware of multiple backend servers and chooses one to use for each RPC. The client gets load reports from backend servers and the client implements the load balancing algorithms. In simpler configurations server load is not considered and client can just round-robin between available servers. This is shown in the picture below. As you can see, the client makes request to a specific backend (#1). The backends respond with load information (#2), typically on the same connection on which client RPC is executed. The client then updates its internal state.

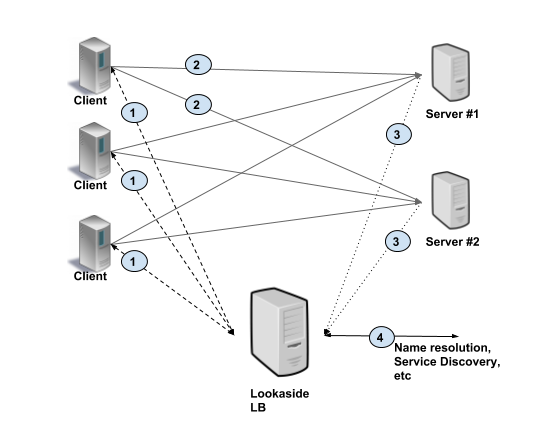

The following table outlines the pros and cons of each model. Proxy load balancing can be L3/L4 (transport level) or L7 (application level). In transport level load balancing, the server terminates the TCP connection and opens another connection to the backend of choice. The application data (HTTP/2 and gRPC frames) are simply copied between the client connection to the backend connection. L3/L4 LB by design does very little processing, adds less latency compared with L7 LB, and is cheaper because it consumes fewer resources. In L7 (application level) load balancing, the LB terminates and parses the HTTP/2 protocol. The LB can inspect each request and assign a backend based on the request contents. For example, a session cookie sent as part of HTTP header can be used to associate with a specific backend, so all requests for that session are served by the same backend. Once the LB has chosen an appropriate backend, it creates a new HTTP/2 connection to that backend. It then forwards the HTTP/2 streams received from the client to the backend(s) of choice. With HTTP/2, LB can distribute the streams from one client among multiple backends. A thick client approach means the load balancing smarts are implemented in the client. The client is responsible for keeping track of available servers, their workload, and the algorithms used for choosing servers. The client typically integrates libraries that communicate with other infrastructures such as service discovery, name resolution, quota management, etc. Note: A lookaside load balancer is also known as an external load balancer or one-arm load balancer With lookaside load balancing, the load balancing smarts are implemented in a special LB server. Clients query the lookaside LB and the LB responds with best server(s) to use. The heavy lifting of keeping server state and implementation of LB algorithm is consolidated in the lookaside LB. Note that client might choose to implement simple algorithms on top of the sophisticated ones implemented in the LB. gRPC defines a protocol for communication between client and LB using this model. See Load Balancing in gRPC doc for details. The picture below illustrates this approach. The client gets at least one address from lookaside LB (#1). Then the client uses this address to make a RPC (#2), and server sends load report to the LB (#3). The lookaside LB communicates with other infrastructure such as name resolution, service discovery, and so on (#4).

Depending upon the particular deployment and constraints, we suggest the following.

Proxy

Client Side

Pros

Cons

Proxy Load Balancer options

L3/L4 (Transport) vs L7 (Application)

Use case

Recommendation

RPC load varies a lot among connections

Use Application level LB

Storage or compute affinity is important

Use Application level LB and use cookies or similar for routing requests to correct backend

Minimizing resource utilization in proxy is more important than features

Use L3/L4 LB

Latency is paramount

Use L3/L4 LB

Client side LB options

Thick client

Lookaside Load Balancing

Recommendations and best practices

Setup

Recommendation